School-Wide Transformation for Multilingual Learners and ALL in the Community!

By Sarah Bernadette Ottow

Multilingual learners, also known as English Language Learners (ELLs) or English Learners (ELs), are not a problem to be fixed but an opportunity to transform a school community for the better. As a rapidly growing, very diverse subgroup speaking over 400 languages in US schools, educators have an opportunity to not just honor and integrate the strengths and needs of our language learners but to leverage this diversity towards positive school-wide transformation for the entire population. How can teachers and leaders help transform their school for the benefit of their multilingual learner population and the entire community as a whole? Below I’ll present three strategies with corresponding resources for deeper learning.

Strategy #1: Embrace change as an opportunity

In my work as a coach and professional learning specialist, I meet teachers and school leaders every day who share how their population of language learners is growing, and, with that, many challenges arise. As the saying goes, with challenges come opportunities. When we are working with students who mirror the increasing diversity of our country and the world, I recommend first tuning our mindset. A proactive, can-do mindset of “What can we learn? What can we improve?” is key, as opposed to a more reactive or negative ways of thinking and acting. All too often in schools, we “admire the problem” over and over until we have looked at it from every direction that we can see a way forward anymore or we don’t even have a goal to reach (“it” often being a student or a population of families). Being reactive is neither productive nor student-centered.

For instance, if one says, “We are being inundated with Newcomers!! We are totally overwhelmed,” this is a very different message than, “At our school, we are working hard to welcome all the Newcomer students and families new to not just our community, but new to our country. It must be so challenging for them. We are trying to listen to their stories and learn what their hopes and dreams are so that we can better support them.” The first message indicates a reactive and almost negative tone, implying that the immigrant population are a stressor, an inconvenience, even an imposition. This approach could even be interpreted as anti-immigrant, anti-multilingual learner, anti-change. Whereas, the second message provides a more proactive standpoint where we realize we, as educators, we are here to support, to learn, to change, and to grow for the better especially when demographics change.

What’s more is that it’s not about us, it’s about the students. The students and families are our end users, our clients, and everyone working for a school community needs to have an end-user-centered, a client-centered mindset focused on meeting students’ needs while also acknowledging and addressing the challenges that come with that change.

How do we embrace change? How do we see change as an opportunity? Using a sphere of influence approach, I urge educators to mentally map out what they truly cannot influence, what they can influence and even what they might be able to influence in time. Here is an example from a group of ESOL teachers I recently worked with. You can see that issues like scheduling and budget needs are not able to be addressed, yet sharing scaffolds with non-ESOL teachers, being an ambassador for students, and taking care of oneself are all within these teachers’ spheres of influence. It turns out we can actually do a lot!

In my view, have a moral obligation to bring an equity-based mindset to each and every student and family we serve. When we are intentional about our mindset, we can move from otherizing to humanizing and fostering a sense of belonging for all learners. Leaders and teachers alike can keep their focus on what they can do and model this for others so as to not inadvertently contribute to negativity or even just getting stuck in admiring the problem. Whether we mean to or not, we may actually contribute to the very challenges that already exist by focusing on what we cannot do anything about, at least not right now. We have a choice, we can shift the focus.

As leaders and even as teachers who identify as teacher leaders, we can really change the narrative by modeling proactive and inclusive language. We can stop and thank a student, a colleague, ourselves. As I like to say, Kids don’t care what you know until they know that you care. The same is true for us as adults and the change begins with us.

Strategy #2: Set the vision for access for all

Once we have the right mindset, how do we bring everyone in a school along so that multilingual learners can learn to their potential? Setting a clear, descriptive vision of what we want for all students (and families!) is key. When supporting teams in this process, I always start with a set of three questions to collectively answer so that we can calibrate around what we all want students to experience in any classroom in the school. Those questions are:

What does instruction where everyone belongs look like?

What does instruction where everyone belongs sound like?

What does instruction where everyone belongs feel like?

Here is an example of a shared vision of instruction from a brainstorm with a group of coaches I recently worked with:

As previously mentioned, language is powerful and can connote a specific mindset or tone, whether it’s intentional or not. When we aspire to bring along all members of a school community, we need to continue to keep language in mind. By engaging in this visioning activity, teams of educators can clarify misconceptions around terminology and practices. For example, What do we really mean when we say “Tier 1” or “mainstream”? I believe that sometimes when we say “mainstream” or “regular” education we are meaning those who don’t fit the mold and we are not including all learners. In this passage from my book The Language Lens for Content Classrooms: A Guide for K-12 Teachers of Language Learners (pages 11-12), I explain:

Which term or terms have you heard to represent the content [Tier 1/universal instruction model] classroom? What comes to your mind when you say the words general or regular or mainstream? What exactly do we imply when we say general, regular, or mainstream education? In my work, I’ve heard all these words, which can imply it is designed for students who meet the description of being from the dominant culture—which, historically speaking, has come to mean English-as-the-first-language, monolingual, white, middle-class, nondisabled students. What I invite you to consider is that, now in this twenty-first century, in our global society, our demographics are changing, the world is getting flatter, and, in turn, our culture is shifting. So in response to these shifts, we need to change our classrooms. Schools need to operate less like twentieth century models and more like ones that value and reflect our changing world.

Have you ever heard the saying that schools are a microcosm of society? Well, if our society is reflected in our schools and our schools are more and more comprised of multilingual, multinational, multiracial, multiethnic, multicultural, multiabled, multiclass populations, we should rethink the language that we use to describe our educational institutions, including our classrooms and our programs. Thus, I offer a new paradigm for what “general education” or “mainstream” classrooms can actually be...I challenge you to use the word general, not regular (what is a “regular” student anyway?), until we come up with more innovative, accurate language as our institutions change to reflect our changing paradigm. Let’s embrace the rich variety that our society brings to our classrooms, and ensure that all teachers, not just language specialists, see themselves as educators who welcome, reach, teach, and celebrate diverse learners, all learners. After all, just because this paradigm is what has been done historically doesn’t mean we can’t change it, working toward more collaboration and culturally and linguistically responsive instruction in every classroom by every teacher!

When we break down silos between general education teachers and those who are specialized as teachers of language learners and special education students, we foster a sense of collaboration and belonging at the universal/Tier 1 level. We can then build a shared toolkit reflecting a shared vision of our collective responsibility to work with all learners. From a language equity perspective, I believe that when we see how all learners are learners of language, we can build shared systems and practices for success. You see, all students are learning academic language. We have students who are Academic Language Learners (ALLs) and those who are learning in English as an additional language are ELLs/multilingual learners. When we break down silos, we can more effectively address the shifts of content standards strategically and intentionally together to support all learners through what I call a “language lens,” explained more in depth in my book.

How does language and literacy fit into every classroom? Well, let’s not forget the key shifts of the content standards (most clearly expressed in the Common Core State Standards) are as follows:

a greater emphasis on literacy and language, including more focus on speaking and listening skills, as well as academic language in general in all content classrooms

a spiraling of complex text types across content areas from K–12

a focus on text-based argumentative text or persuasive writing across grade levels

Once we are clear on our vision of instruction for all language learners, we can create learning environments that support all learners while layering in specific supports for those who need more. Even if we are not formally co-teaching language learners, we can still build systemic supports for both teachers and students that foster growth. A vision that expects reading, writing, listening and speaking in all classrooms enables all students to have access to language/literacy-rich experiences. To have access to language/literacy rich learning in any content area provides students opportunity to learn at high levels and explore all that schools, college, career and life have to offer.

Strategy #3: Showcase growth through multiple measures of data

When we think of data, we may only think of large-scale, summative assessment data, or, often referred to as “big data.” We may feel that the formative measures we use when teaching or when coaching doesn’t count. We may think that only that big data matters. That couldn’t be further from the truth! It’s all data! If you can see it, hear it, even feel it, it’s measurable and it is data. Data equals information. As educators, we are collecting information constantly. I can’t stress enough how important it is to create a fuller, more comprehensive system of data in schools.

For language learners, the need for making more classroom level data visible and valid couldn’t be more imperative. As all students in US public schools at specific grade levels are required by federal law to be assessed by big data annually for proficiency in content areas, so are language learners in their English language proficiency. This large-scale, summative data for language proficiency is is helpful for looking at annual growth but it does little for showing us the nuances of language growth or for providing formative feedback. Like a three-legged table, when we don’t balance this summative data with formative data and interim data, it doesn’t stand. Plus, we take the power away from where it matters most--the classroom.

How do we measure and showcase growth in the classroom? We need to go back to mindset and language, as we explored earlier. If our mindset is, “Only the big data matters because that’s what the state, the school board, and the community looks at,” then we are coming from a mindset that is only looking at data at one point in time. We are valuing proficiency only, we are not valuing growth. To only look at proficiency and not growth is a missed opportunity to be more multidimensional about what really matters--how often we gather data, what kind of data we gather, and who values it. We measure what we value and we value what we measure.

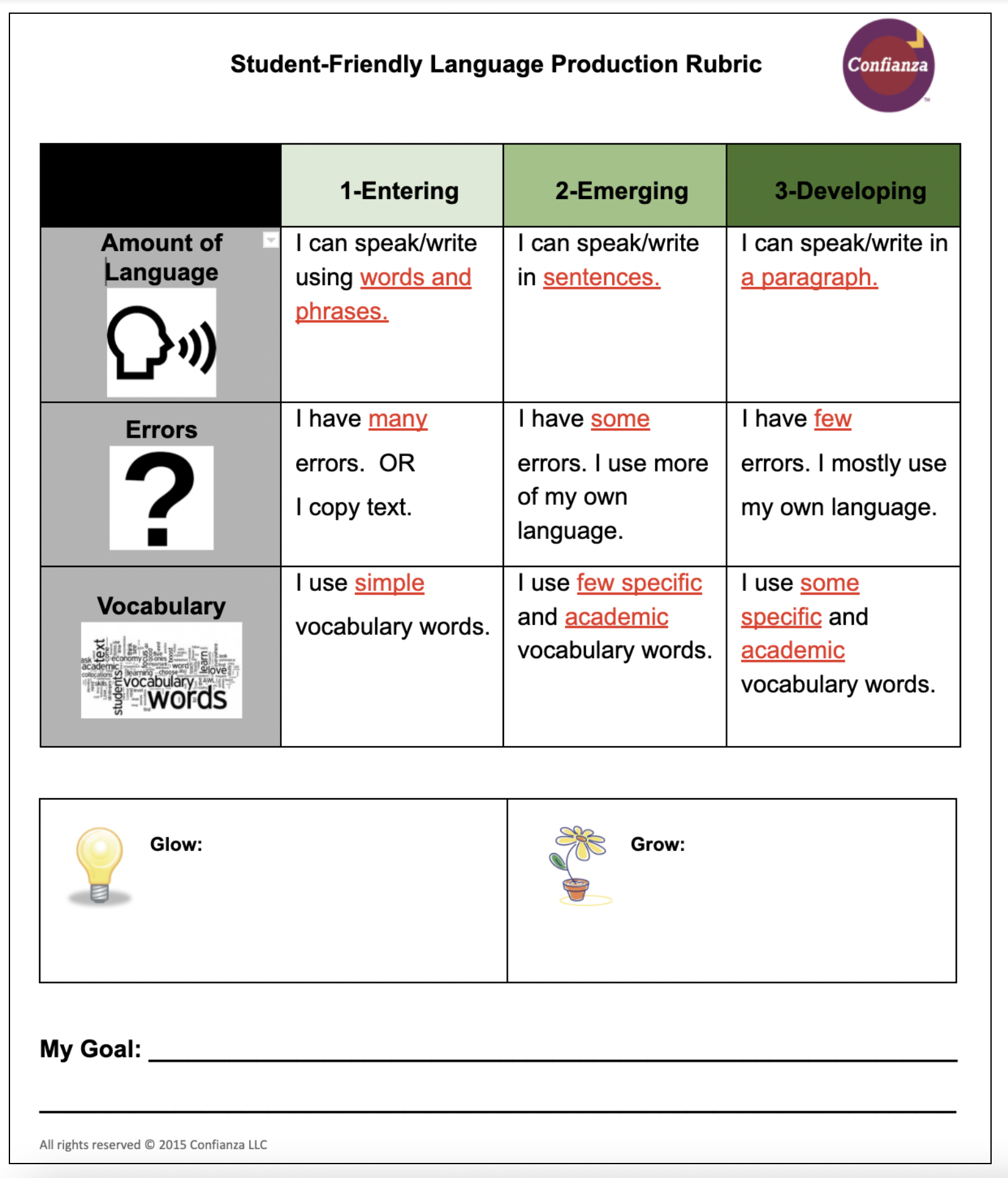

We also need to document the real-time data that is happening in the classroom and create systems to use that data and to really value it. For instance, to support students, What if we had students learning language keep a portfolio? What if we had teachers and students internalize the language proficiency levels so that they could reach for classroom-based growth targets? What if we celebrated this growth on a daily basis as we reached for those longer-term proficiency goals? Then, we would see real growth and real power in the hands of teachers and students. See this student-friendly rubric and goal-setting form below:

For those of us who coach and evaluate, we can also measure the growth of students and of teachers. For instance, to support teachers, if increased student-to-student discourse is part of our vision, we can provide professional learning, including coaching, around how to bring in academic discourse strategies. Coaches and leaders can then, through inquiry cycles, observe and collect classroom coaching data around student discourse to help teachers improve. Here is an example from a coach I work with who is collecting data around number of students annotating which is than also supported by large-scale, interim data (in this case, data from iReady):

In this case, we are measuring real-time classroom data around annotation skills. But we can quantify anything, including the percentage of students on-task, or engaging in authentic student-to-student discourse, or able to articulate the learning goal and purpose, etc. We also cultivate a school culture around noticing and celebrating big and small wins. We can do this at the classroom level through student goal setting and “shout out’s” between students, yet we shouldn’t limit these practices to students. As an adult community of learners, we all need to feel like we belong, we all need psychological safety to do our work well, and we all need to be recognized for our growth, not just our proficiency.

A final word as you move forward

Connecting with students and families is at the heart of teaching and learning. To connect authentically with students and to stand in solidarity with them, we must step out of our own comfort zones and try our best to understand and integrate others’ perspectives beyond not being proficient in our dominant language of English--including those from various and intersecting social identities including race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, gender identity, sexual orientation, socio-economic status and physical, emotional, development ability and health status. In other words, as a White woman, I have to constantly put my experiences aside and consider, “Who are the teachers and leaders I am supporting? Who are their students and families they serve? Are we integrating all students’ and families’ voices into our school’s vision and our daily practices?” To ask these questions constantly and be in a perpetual state of improvement is to start to center those who are historically the most marginalized. When we do that, we all learn, we all transform.

A condensed version of this blog can be found at Learning Forward.

More Learning Forward Blog posts by Sarah B. Ottow:

More about what English learners need now.

More about what instructional leaders need now.

More about a school-wide approach to supporting ELs.