Tips for Comprehensible Instructional Language

by Sarah B. Ottow

Adapted fromThe Language Lens for Content Classrooms by Sarah B. Ottow.The term Language Lens™ is a trademarked term from Confianza’s Framework for Equity, Language & Literacy.

When we teach, we broadcast a message. We want that message to be comprehensible to students. When we broadcast our message, we are expecting students to interpret that message through their input channels of listening and/or reading. We also want them to interact with the message so they actually get to process it and learn it through the output channels of speaking and/or writing.

Review the following six tips for making your instructional language more comprehensible. As you read, you may want to reflect on your own instructional language. If you are a coach or evaluator, you can use these tips when you observe teachers as you support their development. Either way, you may want to record teaching to really slow down and analyze instructional language from students’ perspectives!

TIP 1: Be aware of the rate of speech you use when instructing.

Let’s start by talking about our talking. The sheer fact is that many of us, as teachers, talk really fast. I know I’m guilty of it and need to check myself. We also may mumble and string key words together in what linguists call connected speech so that all the words stick together, like Howzitgoin? or The oppozitofup is down. A student listening to these sentences may hear the word zit when it’s actually not a word spoken here.

We blur words and phrases together in speech, and while that’s how language works and how we want our students to speak as they become proficient, we don’t want our speech to be a barrier to learning. We also don’t need to shout, especially when working with a child who is learning English as an additional language.

TIP 2: Be aware of the amount of speech you use when instructing.

Another factor in our speech is the sheer amount of language we use. While we don’t want to water down our instruction, we do want to use our speech as an instructional modality, not overpower students’ auditory processing with too much information at once or unrelated information. For instance:

When you get in groups, first, assign roles. Then, oh wait, that reminds me that last week we ran out of the notecards for the reporters in each group. I forgot to go to the office supply cabinet downstairs, so let me write myself a quick note to do that. Anyway, then, read the chapter, which I think you’ll love because it’s about dogs and we’ve been studying the Iditarod, plus many of you have pets.

You may notice here that there is a lot going on. Rephrasing or even repeating the language can be helpful, but going off on tangents can be very confusing because students may not know what they are—and aren’t—supposed to pay deep attention to. Also, if we are giving directions, let’s “chunk and chew” multiple steps in a process so that students can follow along, plus use pauses and wait time strategically. I like to use my fingers as a nonverbal and indicate First, Next, and Then to indicate separate steps. I also like to have students (or adult learners!) paraphrase the directions to make sure they really understand the process ahead. Instructional language can be just as complex as the academic language in the task! So use the language lens accordingly when speaking, including the amount of speech you’re using. Can you say less with more?

TIP 3: Be aware of the expressions, or idioms, you use when instructing.

It’s incredible how many cultural expressions and idioms are embedded within our language. I encourage fellow teachers to reflect on what they hear come out of their own mouths that may be completely confusing for language learners if they haven’t heard an expression before.

For example:

Every cloud has a silver lining

Get your act together

On the ball

Speak of the devil

Rocket science

Cut corners

Reflect on these and ask yourself, Do these expressions literally make sense? The answer is no; they all have figurative meanings. Idioms are very culturally loaded, so while some do cross languages, many do not. I am not suggesting not using them at all, because they are very important parts of our vernacular. I am simply suggesting that you use your language lens to use them with care and purpose.

Learn more about idioms in the classroom here.

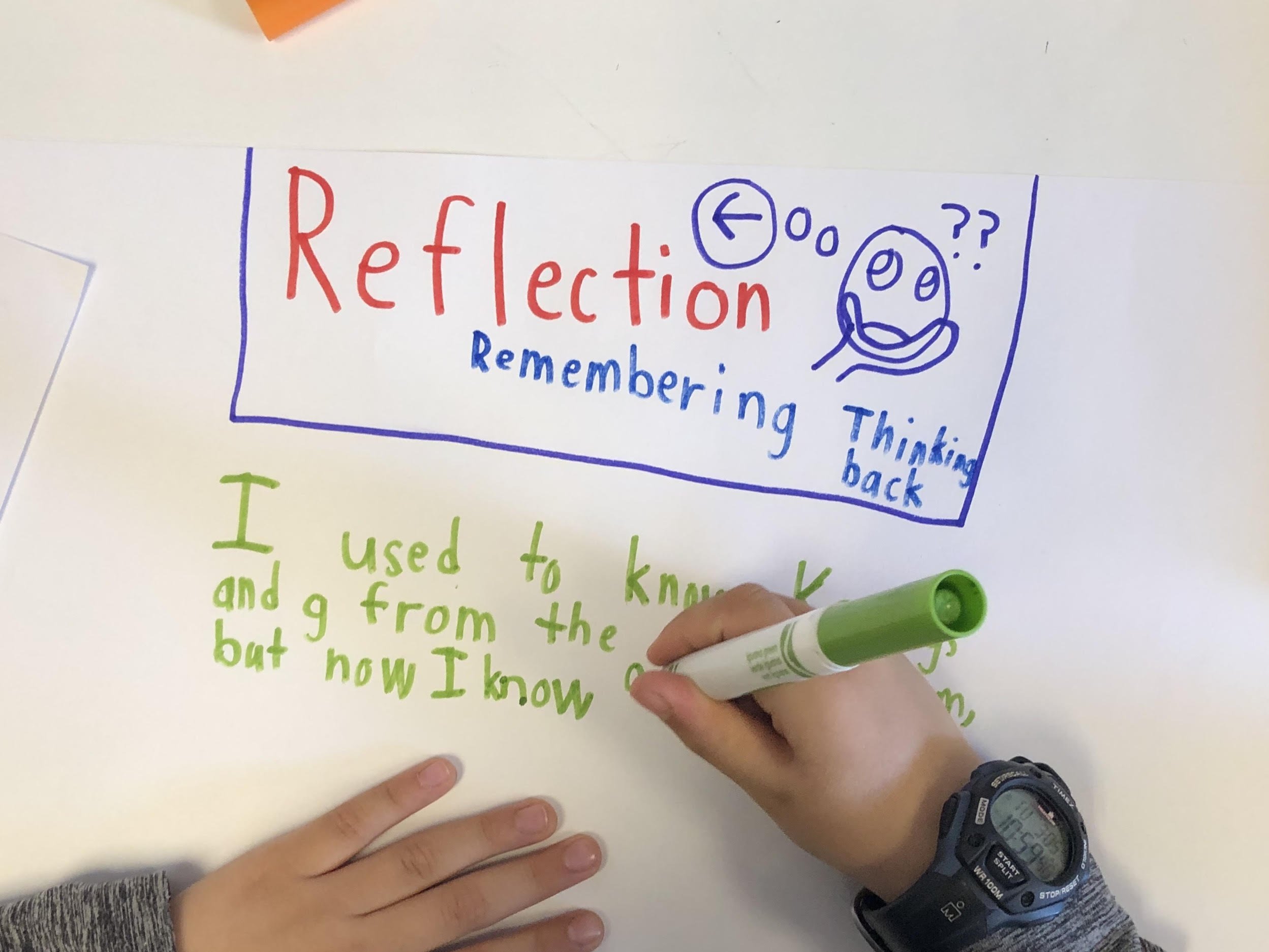

TIP 4: Make learning goals and success criteria explicit for students.

The importance of making language visible that is often invisible for language learners cannot be understated. [Language Learners] benefit from a clear purpose for learning so they know what’s coming and how to see if they made the target or not. Sometimes I walk into a classroom and it’s really unclear what is happening. Students seem unclear, as evidenced by off-task behavior or general looks of confusion. More than anything, one can see that there is a discrepancy between what is taught and what is learned when the data show it. If an assessment is given and students don’t demonstrate the expected knowledge and skills, many times the instruction is to blame, not the students. Ask yourself the following questions:

Do I make the goals of the unit clear for students?

Is the language of this task clear and is it supported through scaffolds?

Do students know what success looks like in each assignment?

Do I have formative checks along the way for students to show they are on track?

Do I get feedback from my students on my teaching? On the tasks?

TIP 5: Use descriptive feedback and positive language as part of formative assessment.

It cannot be stated strongly enough how important it is to use specific feedback when supporting students, not just general praise like Good job! or You’re smart! Students need a safe classroom environment in which to take risks where information is shared with them about how their efforts are helping—or not helping—them reach the intended learning goals (Wiggins et al., 2012). In fact, effective instruction incorporates consistent feedback to students on their growth, also known as formative assessment.

In reflecting about this practice, I recommend first taking a look at the language—including body language—you use with students. Make eye contact and smile, if that’s your style, to encourage students and let them know you care. However, keep in mind that not all cultures view eye contact the same way, so some students may not make eye contact back, and that doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t respect you. Nodding to show you understand and noticing when students put forth effort, even if it’s not the same kind of effort as other students, is important so that all students feel included as part of the learning community. More than anything, demonstrating a growth mindset (Dweck, 2016) through your language and overall tone is imperative. Students can shut down if they get an inkling we don’t believe they can do it. Plus, I cannot understate the importance of wait time, or giving students a chance to deeply process before responding. Make this practice a part of class discussions, group work, and one-on-one feedback sessions.

The language you use in your formative assessments matters, both for written and verbal feedback. Use pointed data to share next steps and encourage student construction of goals going forward. When working one-on-one, instead of Nice work! try, You wrote the word grand here. I can see that you thought it would be a stronger word here than good, which we’ve talked about as a goal for your writing. Nice work taking that extra step to improve your word choice!

When closing up a lesson with the whole class, instead of, It was too loud today during work time. Let’s do better tomorrow, try, I noticed that four out of five groups were focused on the project while I was working with the fifth group. However, those four groups didn’t all seem to be following our protocol in terms of having one student talk at a time. Does anyone have ideas about how we can improve on that tomorrow? Instead of You didn’t spell it right, try You didn’t spell it right yet; how can we make sure you remember this tricky word?

Learn more about descriptive feedback here.

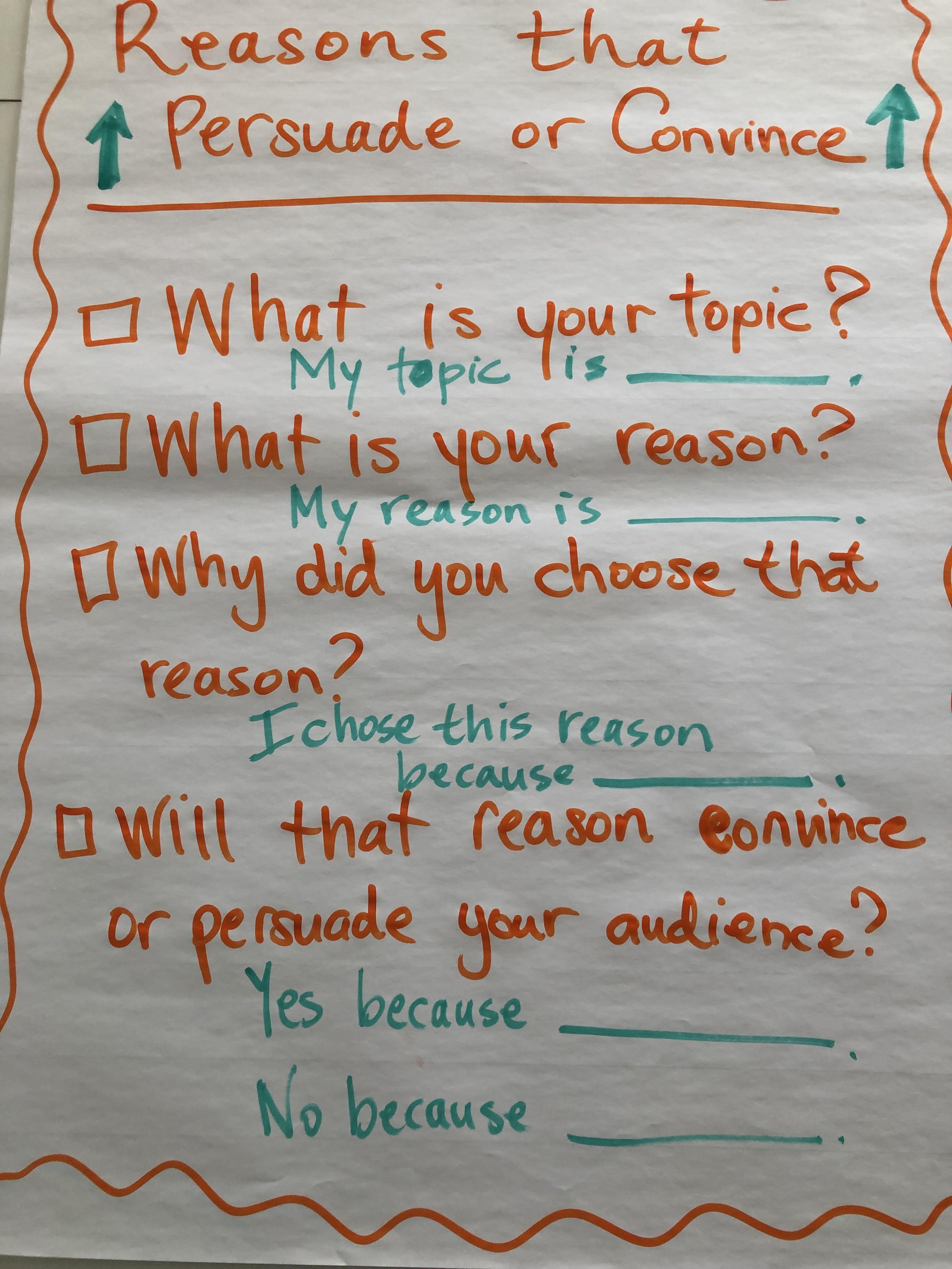

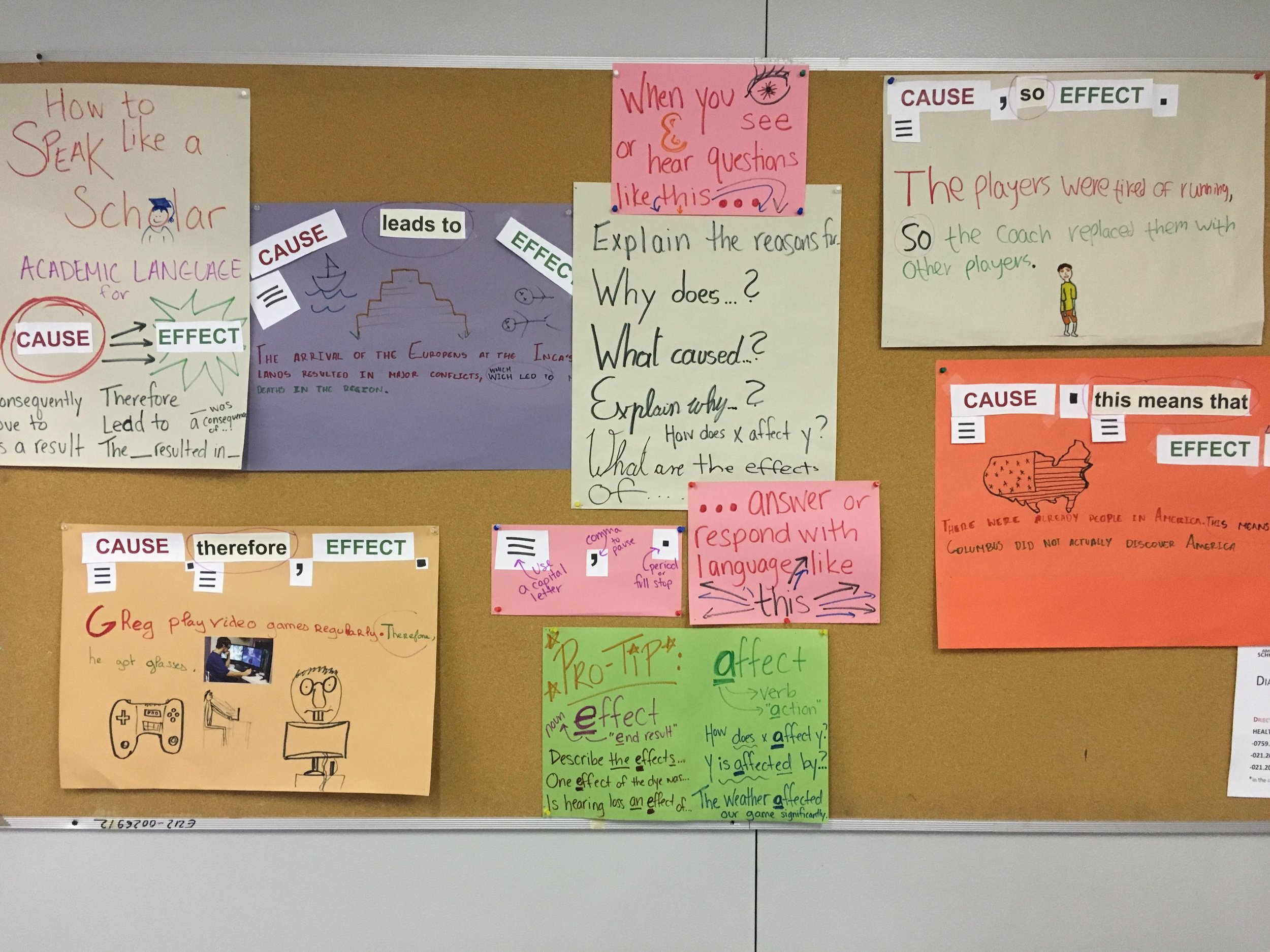

TIP 6: Connect speech to text by posting anchor charts or key words and phrases.

One key way of making speech more comprehensible for students is by connecting print, or text, to oral language as much as possible. To use the earlier example of the teacher giving a task for reading about the Iditarod, I recommend posting a numbered list of the tasks. I would also have student tools in the groups for the roles expected as they read, including key sentence frames for discussion (e.g., This paragraph is about . I agree with because in the text it says on page ___ ). By making instructional language visible, we are giving our language learners more of an opportunity to be successful as they learn new content.

To connect speech to text that is content-related, a common strategy that can work in K–12 is the explicit use of anchor charts. Anchor charts are posters co-created by the teacher and students to make content more comprehensible. They can also be created on slides online or with other tech tools. Remember that when hearing new language, all learners need to see it—and hopefully read and write it as well. It takes multiple exposures and meaningful uses to really learn a new word for any learner. Multilingual learners need even more context, even more repetition, even more connection across the domains of reading, writing, listening and speaking. Plus, our ALLs (Academic Language Learners) benefit as well!

Whether we’re teaching young learners, adolescents or adults, we all need to be cognizant of how our message is received. The whole point of using language when we instruct is to be understood. As you reflect on these six tips, I hope you have found some useful reminders or new information to take with you to help your students learn to their potential!